The rise of renting in the U.S. isn’t just about high housing prices, or preferences for city living, but about the flexibility to compete in today’s economy.

The American Dream has long been defined by homeownership, but current trends suggest this aspiration is waning. The U.S. appears to be undergoing a gradual, long-term shift from a society of mostly homeowners to more of a mix of homeowners and renters. This shift is not just about rising home prices, or a greater demand for urban living, but rather the transition from the old industrial economy to the new, highly clustered, knowledge-based one.

The national homeownership rate has plummeted over the past decade, from an all-time high of 68.8 percent in 2005 to 62.7 percent in 2015. That’s lower than the rate in 1985, when homeownership stood at 63.5 percent.

But the shift from owning to renting a home is much more dramatic in certain cities, and the most innovative and dynamic metropolitan areas consistently post the lowest homeownership rates. My Martin Prosperity Institute colleague, Karen King, and I used Census data to dig into the extent of this great housing reset across American metros from 2000 to 2015—a period that includes the economic crisis of 2008 and the subsequent recovery.

Over this decade and a half, the homeownership rate declined in 90 percent of all American metros (343 of 381) and in 96.2 percent of large metros with more than 1 million residents (51 of 53).

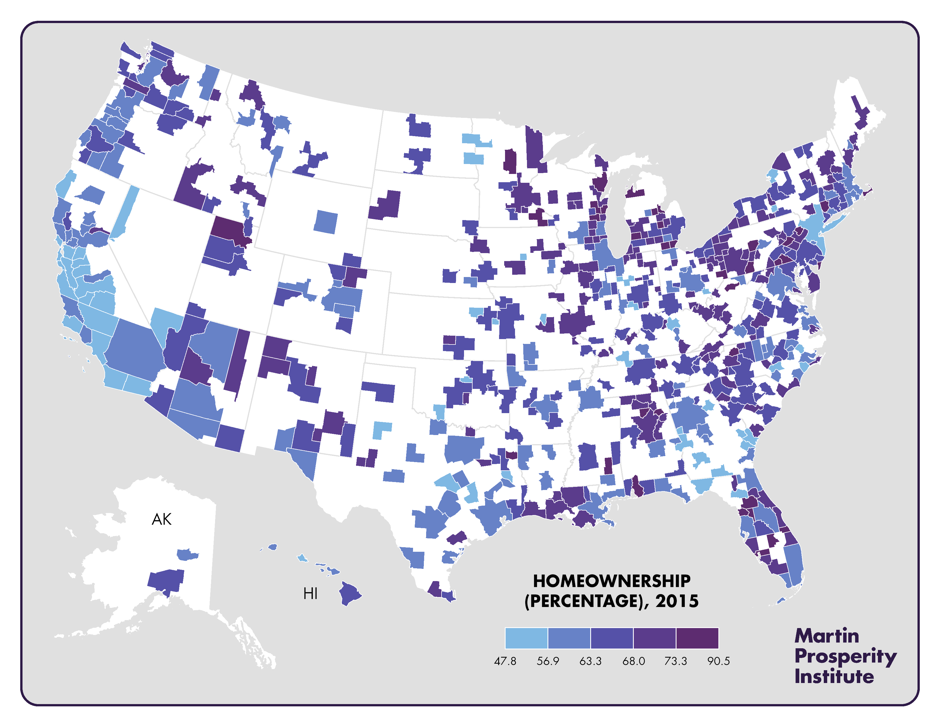

The map above shows the rate of homeownership for U.S. metros in 2015. With the exception of Las Vegas, whose unique service economy includes many transient workers, the lowest levels of homeownership are, generally speaking, in expensive superstar cities and knowledge hubs on the coasts.

Less than half of Los Angeles residents are homeowners, and just about half of people in the New York metro are. The homeownership rate is 52 percent in San Diego, 53.5 percent in San Francisco, 56 percent in San Jose, and 57.5 percent in Austin. Even after the foreclosure crisis, homeownership rates remain much higher in Rust Belt metros: 72 percent in Grand Rapids, 69 percent in Pittsburgh, Birmingham, and Minneapolis–St. Paul, and 68 percent in Detroit and St. Louis. Smaller metros in the Rust Belt and retirement communities in Florida top 75 or 80 percent.

The homeownership rate is lower in America’s more dynamic, more innovative, and more knowledge-based metros. This a product of the fact that these metros are more expensive, but it also speaks to their urban form. Having a larger stock of rental (usually multifamily) housing helps provide the flexibility required to absorb the young people and mobile talent that fuel their economies.

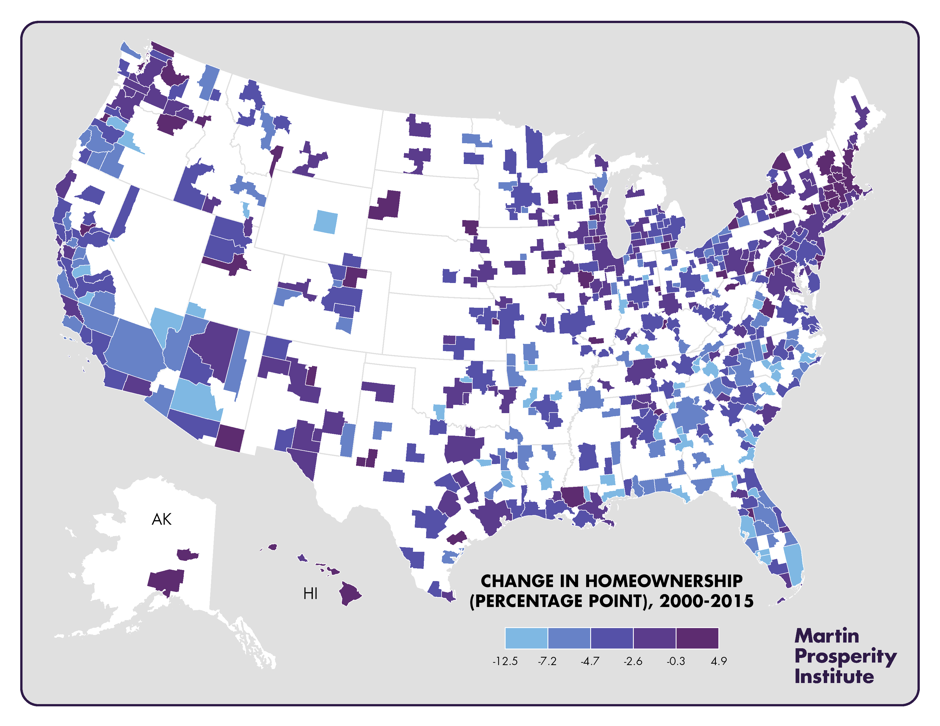

The next map sheds additional light on the great housing reset, charting the change in the homeownership rate between 2000 and 2015. While coastal superstar cities and knowledge hubs have the lowest overall rates of homeownership, the places with the biggest declines are mainly located in the Sunbelt and Rust Belt, where rates had the furthest to fall.

The large metros with the biggest declines in homeownership are Tampa, Las Vegas, Miami, and Phoenix, all of which saw their homeownership rates decline by 7 or more percentage points. The rate declined by 5 points in Atlanta and 4.5 points in Detroit.

In superstar metros and knowledge hubs, rates barely budged, or declined much more modestly. Homeownership declined by just 2 percent in San Francisco and Seattle and just 1.5 percent in Washington, D.C. The rate stayed roughly the same in New York, Austin, Boston, and Hartford. The latter two metros registered increases of tiny fractions of a percentage point, making them the only large metros that saw their rates increase over the study period.

Nearly three-quarters (72.4 percent) of larger ZIP codes (those with at least 1,000 occupied housing units) across the nation saw their homeownership rate decline between 2000 and 2016, according to a Trulia analysis. Homeownership has declined by more than 30 percent in some of these ZIP codes, which include North San Jose, Riverview in St. Louis, and Maryvale in Phoenix. One thing these disparate places have in common: an influx of multifamily rental units. Indeed, a major aspect of the great housing reset is the gradual shift away from single-family-home construction and an increase in multifamily development.

The neighborhoods where homeownership has increased substantially tend to be rapidly gentrifying areas. These have experienced an influx of wealthy owners who have displaced less advantaged renters. An example is the neighborhood surrounding Georgia Tech (the Georgia Institute of Technology) in Atlanta, where homeownership increased from 13 percent to 32.5 percent as median incomes tripled.

The great housing reset varies across class, race, and demographic lines as well as geographic lines, according to the Urban Institute. The homeownership rate among younger Americans between the ages of 25 and 34 declined from a high of almost 50 percent in 2005 to just 35 percent in 2015. It plummeted almost as much among those ages 35 to 44, falling from 69 percent to 56 percent.* It fell from 68 percent to 60 percent for high-school graduates and from 57 to 49 percent for those who never completed high school. And although the rate also went down slightly for college graduates over this 10-year period, it actually rose for them over the broader three-decade period of 1985 to 2015, which is not the case for the previous two categories.

While homeownership declined for all racial groups during the great recession, African Americans are the only group with a lower homeownership rate than they had in 1985. Still, the Urban Institute analysis finds that demographic factors account for only a small amount of the change in homeownership, which is due more to the broad restructuring of the U.S. economy. Another report shows that today’s home buyers are much more likely to be women, or couples without children.

At the risk of stating the obvious, renting has increased substantially across metros as the homeownership rate decreased. Between 2006 and 2016, 22 of America’s 100 largest cities went from being majority-homeowner to majority-renter, more than doubling the initial number of majority-renter metros. The growth in renting outpaced the growth in homeownership in 97 of these cities, according to an analysis by Rentcafe.

Toledo, Memphis, Tampa, Hialeah, Stockton, Honolulu, and Anaheim each saw a 25 percent or more increase in renters over this period. Another dozen or so cities saw their share of renters increase by between 10 and 25 percent, among them Detroit, Cleveland, Columbus, St. Louis, Baltimore, and Minneapolis. Even more striking, the analysis found that 97 percent of the nearly 24 million new residents the U.S. added over that same period are in rental households.

Yet despite widespread declines, homeownership is not becoming obsolete. In fact, the national rate saw a small uptick in 2017 and early 2018, rising to 64.2 percent, alongside a modest decline in rental households. A large proportion of households will continue to choose homeownership, whether in urban condominiums or suburban single-family homes. But the historic ratios between homeowner and renter households will likely continue to shift—in a process that is still in its early stages. And, of course, the balance will continue to vary widely across cities and metro areas.

Great resets are generational events representing an adjustment to a new economy. We are still in the middle of the shift from an industrial system that was powered in large part by suburban homeownership—and the demand for manufactured products it helped create—to a new, highly clustered knowledge-based system in which cities are the basic platform for economic activity. The shift from homeownership to more flexible rental housing reflects the realities of that broader transformation.